Author: Brian Dugger / July 9, 2019

Mark VanWinkle is no stranger to back surgeries. He has had nine of them.

The surgeries and ensuing pain and rehab have been a part of his life since 2003, the unfortunate byproduct of spinal stenosis.

But something was very different about the aftermath of his July, 2013, surgery, in which a surgeon implanted plates, screws and other hardware. By Labor Day, VanWinkle says, it felt as though he was getting stabbed – over and over.

The hardware had come apart. When surgeons opened him up, an extremely dangerous infection – Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, or MRSA – was discovered.

“The infectious disease doctor said it had been introduced during the surgery in July and was a slow-growing infection, similar to acne,” Diana VanWinkle, Mark’s wife of 30 years, tells 11 Investigates. “They don’t think it was from him. It was from the surgery.”

Mark and Diana VanWinkle discuss Mark’s back surgeries and the subsequent infection he’s fighting.

WTOL

There is no way to say for sure what caused VanWinkle’s illness, but infections are not uncommon after spinal surgeries. A randomized trial of 314 patients released in 2016 by a team of doctors found that 12.7 percent of patients suffered an infection after a spinal fusion. That means more than 120,000 infections a year in the United States. For surgeries involving scoliosis patients, research has put the infection rate at between 25 and 40 percent.

“It was three months of antibiotics through an IV. Day in and day out, it was huge amounts of antibiotics,” Mark VanWinkle says. “I didn’t leave the house. I didn’t go outside. I didn’t leave the chair that I lived in for months.”

There is no way to say for sure what caused VanWinkle’s illness, but infections are not uncommon after spinal surgeries. A randomized trial of 314 patients released in 2016 by a team of doctors found that 12.7 percent of patients suffered an infection after a spinal fusion. That means more than 120,000 infections a year in the United States. For surgeries involving scoliosis patients, research has put the infection rate at between 25 and 40 percent.

“It was three months of antibiotics through an IV. Day in and day out, it was huge amounts of antibiotics,” Mark VanWinkle says. “I didn’t leave the house. I didn’t go outside. I didn’t leave the chair that I lived in for months.”

Eventually, his FMLA benefits ran out, and VanWinkle lost his job of 23 years.

“We could have easily lost everything,” Diana VanWinkle says.

It is pain and suffering that, in many cases, can be avoided, a local researcher believes.

Aakash Agarwal, an adjunct professor of bioengineering at the University of Toledo and the director of research for Spinal Balance Inc., is driven by the goal of driving down infection rates. While not the main reason for his research, his grandmother died from an infection after a hip transplant. Agarwal’s belief is that almost all infections result from bacteria being introduced into the body during a procedure.

“There is evidence that most orthopedic devices used during a surgery are contaminated,” Agarwal tells 11 Investigates.

Regarding spinal surgeries, Agarwal’s focus has been on the pedicle screw. The screws are used for stability and support in spinal fusion surgeries. But Agarwal believes the screw can be a vehicle for infection, providing a pathway for dangerous bacteria.

But how does that bacteria appear on a screw in what is supposedly a sterile environment?

A surgeon has more than 100 screws of varying sizes available to him during a surgery.

“But about six are used in surgery. The rest are recycled. They are washed again with the dirty implements from the surgery,” Agarwal says.

Every screw that is not used during the surgery is required to go back into the hospital’s sterilizer – a dishwasher-like machine. It’s a procedure that some of the screws can go through up to 50 times before being put into the body. Several studies have agreed that, over time, the process can result in corrosion and bacteria on the screws.

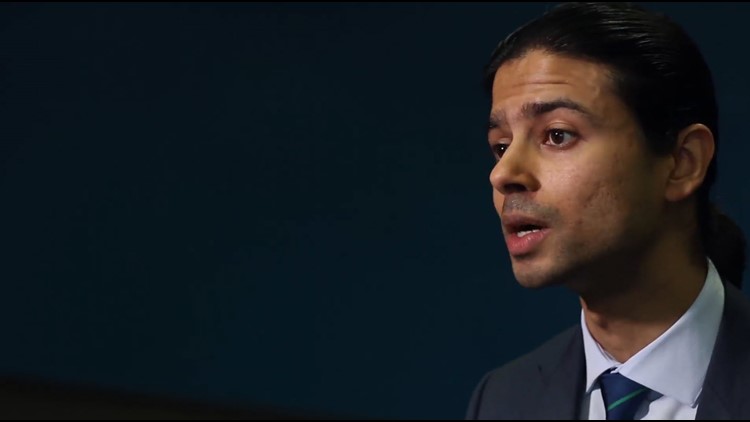

Aakash Agarwal, is an adjunct professor of bioengineering at the University of Toledo and the director of research for Spinal Balance Inc.

WTOL

Agarwal led a multicenter study that was released in a number of journals last year, including Global Spine Journal. His study used an electron microscope to examine pedicle screws awaiting implant from surgical trays. The study was funded by the government’s National Science Foundation, of which Spinal Balance is a member.

“We randomly selected screws and opened it up and found things that we should not be finding,” he says

Tissue. Fat. Corrosion. Soap.

During repeated washings with bloody surgical tools, Agarwal believes material can get trapped in the many nooks and crannies of a pedicle screw.

His study noted that manufacturers recommended 19 man-hours to sterilize the screws. His team’s observation was that a little more than an hour was being used on the process.

While Agarwal’s research targets pedicle screws, the same procedure is followed for some orthopedic screws, particularly those used in trauma surgeries.